Digital training improves dental care, turns students into inventors

The patient needed dentures, but he couldn’t afford them.

So dental student Adam Robinson, drawing on what he learned in an Adams School of Dentistry course, created a virtual 3D model of the man’s mouth and saved the image file. Robinson then uploaded the file to a dental fabrication lab, which used a 3D printer to produce a set of dentures for the patient.

The process saved time and money, while improving the man’s life and health.

Approximately 90 aspiring dentists like Robinson take courses taught every semester by Dr. Wendy Clark, clinical assistant professor, that blend digital fabrication methods with conventional practices. They learn computer-aided design and manufacturing methods to create dentures and other artificial devices that function in place of missing parts of a patient’s mouth. They train with online tools and in a University BeAM Makerspace in Murray Hall to make devices with a 3D filament printer.

The courses are simultaneously foundational and innovative.

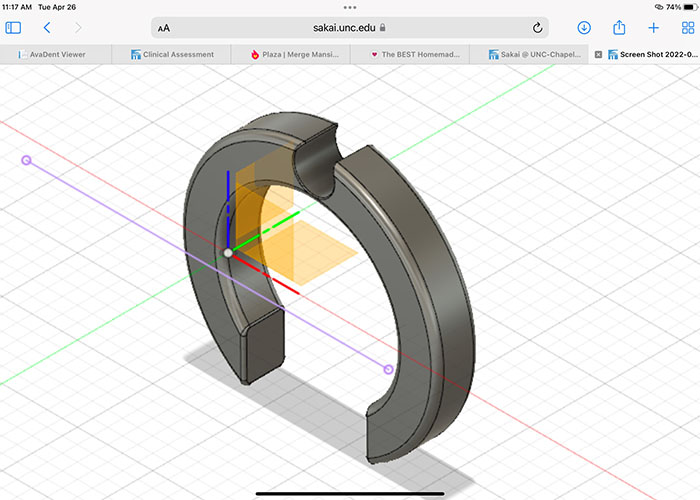

The students also become inventors. Clark has them design, create and patent items that every dentist needs in clinic. They use 3D design software such as Fusion 360 or an online 3D modeling site such as Tinkercad.com. In 2020, Robinson and his classmates in the Complete Dentures class designed trays for making molds of patients’ mouths that can be customized “kind of like Legos,” he said. Others designed drill guards to prevent dentists from poking themselves.

Clark’s students use 3D software to invent devices such as the Cord Cuff, which dental professionals could use to corral and manage all the equipment cords in an operatory.

“The students took to that project,” Robinson said. “We had orientations at the makerspace, and I loved working with Fusion 360. I got really into it. Dentists in general have a conceptual or engineer mindset. That was a lot of fun.”

Students learn more efficient, cost-effective ways of patient care and better understand the business side of practicing dentistry.

Clark, who joined the faculty in 2017, brought her knowledge of digital dentistry and a desire to teach it to students. It wasn’t until after she arrived that Clark learned that the makerspaces existed. She soon felt compelled to point her students to Murray Hall.

“We can get siloed, so it’s really important for the students to get out on campus and see some of the other things. It was beneficial to me to get out to the makerspace,” Clark said.

Now the makerspace is integral to her students’ education. She revamped the course’s curriculum with the help of Anna Engelke, makerspace education program manager, adding CAD/CAM training. “It’s an up-and-coming area of denture fabrication,” Clark said.

Even though the first class met at Murray Hall, the second year changed to all-remote training when the pandemic began. Digital fabrication classes turned out to be a natural fit for remote teaching because of the online tools to facilitate instruction and student work. Instead of fabricating their creations in Carolina’s makerspace, students uploaded files to a commercial lab for printing.

In early spring 2022, a class worked with Engelke via Zoom. The students began by accessing Tinkercad through a link on Sakai. Clark answered questions about taking impressions of patients’ teeth, then set the stage for Engelke.

Clark stresses that students’ creativity shouldn’t end when the class ends. “We should remain makers,” she said, “not just of teeth but also of other cool things.”

The class watched Engelke create a digital model of an earsaver, to which dentists attach mask loops that relieve pressure around their ears. It’s a practical device.

Engelke described for her students the online video modules they would use to certify they can operate the makerspace 3D printer, then shifted to an overview of Tinkercad. She showed them how to build a 3D file of an earsaver that they could upload for printing.

On a virtual plane, she combined brightly colored shapes, stretching and molding them into a 3D strap. “It’s like working with Play-Doh,” she said.

After several modifications, including using a scribble tool to add her name, Engelke gave the earsaver a last look, which yielded another tip. “This is a thin design,” she said. “3D printers are precise, and it’s hard to tell sometimes the way the plastic will melt. If the letters are really small and shallow, you might not get the definition that you want.”

The students were ready for an assignment that Clark would review: Create an earsaver and save it for printing.

Students in Clark’s classes also design products for use in dental clinics. In 2021, they produced a TikTok-style video to demonstrate the products they printed. “Their creativity was off the charts,” Clark said.

Three years in, the class of 2022, which took all of Clark’s digital fabrication courses, graduated on May 6.

“My vision is to teach them this integrated curriculum of foundational methods with the CAD/CAM,” Clark said. “It’s been really cool to see them seamlessly integrate these workflows. Rather than using one cookie-cutter method to make dentures, they think critically about how CAD/CAM might make a certain case better or why a case might not qualify for CAD/CAM.”

In the case of Robinson and classmate Glenn Baldwin, they employed digital methods to help patients at the Durham, North Carolina, CAARE clinic. CAARE provides health care to vulnerable populations.

They manually created molds of patients’ mouths by placing alginate material in u-shaped trays — for lower and upper bites. When patients bite the trays, the alginate quickly gels to form a mold of the mouth. The dental students scanned the models to create digital files, then sent the files to a dental fabrication lab that printed the dentures. “It’s a transition from the makerspace, Tinkercad and Fusion 360 into a direct dental application,” Robinson said.

The digital methods reduced the usual five or six appointments to three or four, saved materials and helped the students make free dentures for 20 people, which would have cost $600 or more.

“The cost doesn’t compare to the real value to the person getting the dentures,” he said.

This article was written by Scott Jared of University Communications and is posted on thewell.unc.edu at this link.